Coral will become deformed and increasingly fall victim to outbreaks of herpes-like viruses as humans continue to pump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to two new studies.

Combined, the two effects suggest coral reefs will have trouble recovering from bleaching events, like the the world is currently experiencing.

When carbon dioxide is emitted from factories, cars and power plants, about 30% of it is absorbed by the ocean. As that happens, the acidity of the oceans increases, which makes it harder for corals to build their alkaline skeletons.

But exactly how the increasing acidity impacts coral growth was hard to determine. “If you just look at survival rates of these things, effectively they all survive,” said Peta Clode from the University of Western Australia. “So if you look at that data you think nothing is wrong.”

Even studies that used microscopes to examine how corals grow in more acidic water had trouble finding differences, she said.

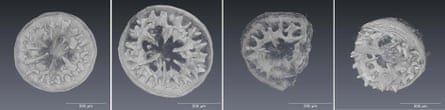

So Clode and colleagues went a step further and grew corals in a range of different temperatures and acidities, and then used a high-resolution three-dimensional x-ray microscope to examine how they grew.

Published in the journal Science Advances on Friday, the images and videos they produced revealed striking deformities in corals grown under conditions the oceans are expected to see by the end of the century.

Under normal conditions, baby corals grew skeletons that were symmetrical, strong and with thick walls.

But when the acidity was raised to the level expected by 2100 if emissions are not cut drastically, the skeletons had some spines stunted in growth, while others grew longer. Some parts of the skeleton were completely absent.

They grew into an asymmetrical shape and their walls became pitted and porous, and half of them had fractures in their deformed skeletons.

“You think ‘oh my god, look at them.’ It is very dramatic,” said Clode. “You would expect they would not grow very well. But to see such deformity is surprising. We expected they might just grow less.”

The effect of heat alone seemed to have little impact, and when combined with high acidity it had a beneficial effect, mitigating some of the deformities caused by the higher acidity.

Clode said that was not completely surprising, since higher temperatures that did not stress coral – temperatures that were not too high or too suddenly raised – had been seen to improve coral growth before.

The results showed that as the ocean acidifies, young coral reefs will have trouble re-establishing after they get damaged by events like bleaching or storms, Clode said.

“The juveniles, they’re the reef formers of the future so to start out at a disadvantage like this, you start to worry about how [much] it can take,” said Tracy Ainsworth from James Cook University in Townsville, Australia.

Ainsworth and colleagues recently published a different paper examining the struggles coral will experience in the future.

They examined the viral loads in corals as they got bleached over three days in 2011 on part of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, publishing their results in the journal Frontiers of Microbiology.

Bleaching occurs when corals are stressed by things including hot temperatures, being exposed to the air, or heavy rainfall that lowers the salinity of the water. Global warming is expected to increase the frequency of bleaching by pushing corals closer to the limits of temperatures they can tolerate.

Ainsworth and colleagues found that as the coral bleached, a viral outbreak occurred. Among the many viruses they saw explode was a big spike in one that was similar to the herpes viruses that infect humans. Viral loads were up to four times higher than has ever been seen in corals before.

Ainsworth said the viral loads of corals during a bleaching event hadn’t been studied before, and outbreaks like this might be normal.

That is bad news since it might be too much for corals to cope with as they bleach more frequently, she said. “When corals are under stress, it’s not just bleaching that they have to overcome,” she said. “It’s coupled with a change in the microbial communities that it has to deal with.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion